Which Should You Use: VARCHAR or NVARCHAR?

You’re building a new table or adding a column, and you wanna know which datatype to use: VARCHAR or NVARCHAR?

If you need to store Unicode data, the choice is made for you: NVARCHAR says it’s gonna be me.

But if you’re not sure, maybe you think, “I should use VARCHAR because it takes half the storage space.” I know I certainly felt that way, but a ton of commenters called me out on it when I posted an Office Hours answer about how I default to VARCHAR. One developer after another told me I was wrong, and that in 2025, it’s time to default to NVARCHAR instead. Let’s run an experiment!

To find out, let’s take the big 2024 Stack Overflow database and create two copies of the Users table. I’m using the Users table here to keep the demo short and sweet because I ain’t got all day to be loading gigabytes of data (and reloading, as you’ll see momentarily.) We’re just going to focus on the string columns, so we’ll create one with VARCHARs and one with NVARCHARs. Then, to keep things simple, we’ll only load the data that’s purely VARCHAR (because some wackos may have put some fancypants Unicode data in their AboutMe.)

Transact-SQL

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 |

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS dbo.Users_Varchar; DROP TABLE IF EXISTS dbo.Users_NVarchar; GO CREATE TABLE dbo.Users_Varchar (Id INT PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED, AboutMe VARCHAR(MAX), DisplayName VARCHAR(40), Location VARCHAR(100), WebsiteUrl VARCHAR(200)); INSERT INTO dbo.Users_Varchar (Id, AboutMe, DisplayName, Location, WebsiteUrl) SELECT Id, AboutMe, DisplayName, Location, WebsiteUrl FROM dbo.Users WHERE COALESCE(AboutMe,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN AND COALESCE(DisplayName,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN AND COALESCE(Location,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN AND COALESCE(WebsiteUrl,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN; CREATE TABLE dbo.Users_NVarchar (Id INT PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED, AboutMe NVARCHAR(MAX), DisplayName NVARCHAR(40), Location NVARCHAR(100), WebsiteUrl NVARCHAR(200)); INSERT INTO dbo.Users_NVarchar (Id, AboutMe, DisplayName, Location, WebsiteUrl) SELECT Id, AboutMe, DisplayName, Location, WebsiteUrl FROM dbo.Users WHERE COALESCE(AboutMe,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN AND COALESCE(DisplayName,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN AND COALESCE(Location,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN AND COALESCE(WebsiteUrl,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN; GO |

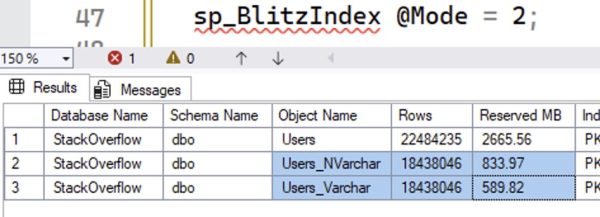

Let’s compare their sizes with sp_BlitzIndex @Mode = 2, which lists all the objects in the database. (I’ve dropped everything else because YOLO.)

The NVARCHAR version of the table is bigger. You might have heard that it’d be twice as big – well, that’s not exactly true because the rows themselves have some overhead, and some of the rows are nulls.

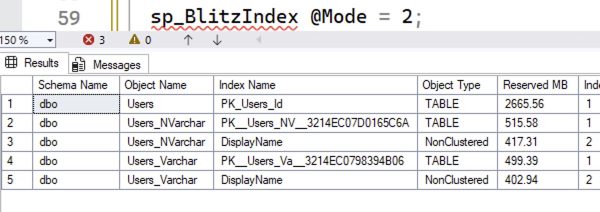

The difference shows up in indexes, too. Let’s create indexes on the DisplayName column:

The NVARCHAR version of the index is 629MB, and the VARCHAR version is 439MB. That’s a pretty big difference.

I used to hate it when people said, “Who cares? Disk is cheap.”

The first problem with that statement is that up in the cloud, disk ain’t cheap.

Second, memory ain’t cheap either – again, especially up in the cloud. These object sizes affect memory because the same 8KB pages on disk are the same ones we cache up in memory. The larger our objects are, the less effective cache we have – we can cache less rows worth of data.

Finally, whether the data’s in memory or on disk, the more of it we have, the longer our scans will take – because we have to scan more 8KB pages. If you’re doing an index seek and only reading a handful of rows, this doesn’t really matter, but the more data your query needs to read, the uglier this gets. Reporting queries that do index scans will feel the pain here.

But then I started using compression.

If you’re willing to spend a little more CPU time on your writes & reads, data compression can cut the number of pages for an object. Let’s rebuild our objects with row compression alone to reduce the size required by each datatype. (I’m not using page compression here because that introduces a different factor in the discussion, row similarity.)

Transact-SQL

|

1 2 3 4 |

ALTER TABLE dbo.Users_NVarchar REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = ROW); ALTER TABLE dbo.Users_Varchar REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = ROW); ALTER INDEX DisplayName ON dbo.Users_NVarchar REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = ROW); ALTER INDEX DisplayName ON dbo.Users_Varchar REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = ROW); |

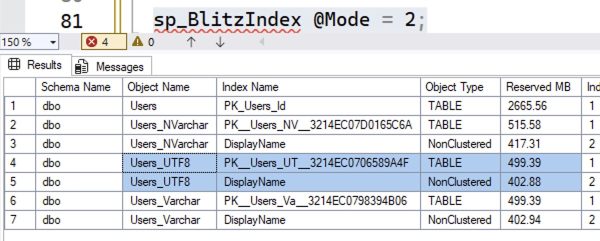

The size results:

Now, the object sizes are pretty much neck and neck! The difference is less than 5%. So for me, if I’m creating a new object and there’s even the slightest chance that we’re going to need to store Unicode data, I’m using NVARCHAR datatypes, and if space is a concern, I’m enabling row compression.

What about the new UTF-8 collation?

SQL Server 2019 introduced UTF-8 support to allow VARCHAR columns to store more stuff. At the time it came out, character guru Solomon Rutzky said it was tearin’ up his heart, concluding:

While interesting, the new UTF-8 Collations only truly solve a rather narrow problem, and are currently too buggy to use with confidence, especially as a database’s default Collation. These encodings really only make sense to use with

NVARCHAR(MAX)data, if the values are mostly ASCII characters, and especially if the values are stored off-row. Otherwise, you are better off using Data Compression, or possibly Clustered Columnstore Indexes. Unfortunately, this feature provides much more benefit to marketing than it does to users.

Yowza. Well, we call him a character guru for more reasons than one. At the time, I wrote off UTF-8, but let’s revisit it today in SQL Server 2025 to see if it makes sense. We’ll create a table with it, and an index, and compress them:

Transact-SQL

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

CREATE TABLE dbo.Users_UTF8 ( Id INT PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED, AboutMe VARCHAR(MAX) COLLATE Latin1_General_100_BIN2_UTF8, DisplayName VARCHAR(40) COLLATE Latin1_General_100_BIN2_UTF8, Location VARCHAR(100) COLLATE Latin1_General_100_BIN2_UTF8, WebsiteUrl VARCHAR(200) COLLATE Latin1_General_100_BIN2_UTF8 ); INSERT INTO dbo.Users_UTF8 (Id, AboutMe, DisplayName, Location, WebsiteUrl) SELECT Id, AboutMe, DisplayName, Location, WebsiteUrl FROM dbo.Users WHERE COALESCE(AboutMe,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN AND COALESCE(DisplayName,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN AND COALESCE(Location,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN AND COALESCE(WebsiteUrl,'') NOT LIKE '%[^ -~]%' COLLATE Latin1_General_BIN; ALTER TABLE dbo.Users_UTF8 REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = ROW); CREATE INDEX DisplayName ON dbo.Users_UTF8(DisplayName) WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = ROW); |

The resulting sizes:

Sure, the UTF-8 versions are about the same as the VARCHAR version – but, uh, neither of those is really a savings compared to compressed NVARCHAR. What if we remove the compression from all 3 versions?

Transact-SQL

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

ALTER TABLE dbo.Users_NVarchar REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = NONE); ALTER TABLE dbo.Users_Varchar REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = NONE); ALTER TABLE dbo.Users_UTF8 REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = NONE); ALTER INDEX DisplayName ON dbo.Users_NVarchar REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = NONE); ALTER INDEX DisplayName ON dbo.Users_Varchar REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = NONE); ALTER INDEX DisplayName ON dbo.Users_UTF8 REBUILD WITH (DATA_COMPRESSION = NONE); |

The resulting sizes:

Like Solomon wrote years ago, UTF-8 really only makes sense when you’re not allowed to use compression for some reason.

The verdict: just use compressed NVARCHAR.

If you’re positive your application will never need to store Unicode data there, sure, default to VARCHAR. You get a disk space savings, you can cram more in memory, and your index scans will be faster because they’ll read less pages. (Not to mention all your maintenance operations like backups, restores, index rebuilds, and corruption checks.)

But you also need to be sure that the application will never pass in NVARCHAR parameters in its queries, which introduces the risk of implicit conversion.

I say if there’s even a chance that you’ll hit implicit conversion, or that you’ll need to put Unicode data in there, just default to NVARCHAR columns. Compress ’em with row-level compression to reduce their overhead to within a few percent of VARCHAR, and that mostly mitigates the concerns about about disk space, memory caching capacity, or long index scans.

Related

Hi! I’m Brent Ozar.

I make Microsoft SQL Server go faster. I love teaching, travel, cars, and laughing. I’m based out of Las Vegas. He/him. I teach SQL Server training classes, or if you haven’t got time for the pain, I’m available for consulting too.

Get Free SQL Stuff

"*" indicates required fields

29 Comments. Leave new

Thanks for going through all the choices, Brent! Is there a reason you recommend row compression over page compression?

You’re welcome. As I wrote in the post, I’m not using page compression here because that introduces a different factor in the discussion, row similarity.

Ah I missed that, thanks!

I would argue using page compression changes the argument so it should be part of this debate. That’s because nvarchar verses varchar when using page compression often still makes a big difference in storage (unlike when using row compression as you pointed out).

OK, cool, you’re welcome to run your own experiments and share them with others on your blog. My experiment is finished here. Thanks!

I stand corrected – my results with page compression on one of our tables was similar. Only @2% difference between datatypes. Dang it! Can I keep my opinion even though the data doesn’t support it? 😉

Row compression: nvarchar = 2,501,576 KB. varchar = 2,441,424 KB.

Page compression: nvarchar = 1,621,896 KB. varchar = 1,589,392 KB.

No compression: nvarchar = 4,533,776 KB. varchar = 2,813,456 KB.

It’s so true – doing the research really helps us break out of bad patterns. That’s how this whole blog post started, too! I was used to saying, “Just use VARCHAR until you need to store NVARCHAR later, and you probably won’t,” but after this experiment, I totally changed my viewpoint. Screw it, just use NVARCHAR.

I’m really new (as in since 3 months) to SQL Server, which is why I spend a lot of time RTFM… It turns out that page compression *includes* row (and prefix) compression, and there is even an extra compression mode for Unicode – which kicks in for in-row NCHAR and NVARCHAR values when row (or, of course, page) compression is used. I’m not sure how this SCSU algorithm differs from UTF-8 but it reportedly achieves similar compression ratios (50%) for Latin-based values.

I believe that type nvarchar() is designed for the global character storage, more general. instead, the varchar() type is good for English language only.

Don’t forget that it’s not just for English. If you want to let your inner-Middle-schooler DBA flag fly, you also need NVARCHAR().

INSERT INTO ?(?) VALUES (N'?');DENIED! Don’t get to play “juvenile fun with emojis” today.

Not quite!

VARCHAR(..) uses a code page depending on the collation sequence in play. However, the common “Latin1” collation sequences (unsurprisingly) use code pages aimed at Latin-alphabet based languages

But a VARCHAR(..) field using, say, Chinese_PRC_CI_AS collation sequence uses (I think) CP936 instead, which is (ultimately) based on the GB2312 character set and handles simplified/modern Chinese glyphs fine.

In other words:

– VARCHAR uses a code page depending on the collation sequence

– NVARCHAR uses UTF-16

– The UTF-8 collation sequence variants cause VARCHAR to use the UTF-8 code page, but have no effect on NVARCHAR.

The advantage of UTF-16 and UTF-8 is “any language in any row” — you can have a single column that has a mixture of Chinese, Thai, Maori, Greek and emojis etc. Traditional code pages struggle, and usually fail, to handle a mixture of languages like that.

This post seemed to be pretty *nsync. Great article and saves the rest of us doing all the work to prove it.

developers wanting to default to nvarchar that don’t know why, to me is just laziness.

To be clear, if there is any doubt at all, I go with nvarchar. But defaulting things like phone numbers (particularly pernicious), internal product names, internal codes used by the business, non-email usernames (not to say that a username can’t be unicode, but they typically won’t be) enums and other things that are just never going to have any unicode characters, including some non-english language businesses that use the latin alphabet, many devs are still going to complain for just because. And you made this point.

I think it is still best to default to varchar even if unicode ends up being more prevalent as the exception than the default. While compression mitigates the storage and memory consumption, I find pretty frequently that when you do aggregation or windowing over compressed string columns, the CPU penalty can be worse than the memory penalty, so you just end up eating more memory.

There is a lot to consider when allowing more than ASCII for usernames (and other attributes you assume is unique). https://engineering.atspotify.com/2013/6/creative-usernames

That was a very interesting article, thanks for sharing!

I really appreciate this post, thanks. My friend has also informed me that there may also be implications of using each of these data types when executing dynamic SQL (EXEC vs. sp_executesql) and the query plans being stored, not not.

Very interesting and useful article on compression. However, I have let it send me down a rabbit hole that lead to a warren. In checking table size changes I discovered my main database is *massively* io-bound, with 21.7ms Avg Read Wait and 1,177.8 Avg Write Wait. Yikes! All the other databases, bar one, are reasonable. Methinks I’ve got some work to do!

Just the fact that you specify say varchar(20), but only fit 19 characters. Or 18. Or 20. Or 17. Etc. It depends.

That alone, if forced to use UTF-8, would make me feel like Sideshow Bob stepping on that rake

[…] Which Should You Use: VARCHAR or NVARCHAR? (Brent Ozar) […]

[…] Brent Ozar asks a question: […]

I’m confused. Why does row compression help? Isn’t the whole point of having a variable length column that you don’t need row compression to save unused space?

Great question! Fire open your favorite LLM, like ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini, and ask how row compression helps. It’s a great way to learn in situations like this.

Row compression activates Unicode compression. Uncompressed Unicode values are stored as UCS-2, or 2 bytes per character. That’s why.

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/sql/relational-databases/data-compression/unicode-compression-implementation?view=sql-server-ver17

How does row compression on NVARCHAR affect CPU performance? Will I save on disk, use memory nearly as efficiently, and allow for unicode characters but need increase my CPU count slightly? Thus increasing my overall cost for licensing?

Eric – that’s beyond the scope of this post. (There are only so many things I can teach y’all in each free blog post – hope that’s fair!)

Compression can cause CPU usage to go up, but it can just as easily cause it to go down. Even taking into account CPU concerns, Kendra Little’s general recommendation (as of 2024) is: “Please Compress Your Indexes and Shrink Your Databases if you use Azure SQL Managed Instance.” This recommendation probably also applies to other cloud hosts.

Here, she was going a step further and suggesting page compression.

Important part of the post: use NVARCHAR only, when there is a chance that it may contain unicode AND you apply at least row compression and ensures that every junior dba follow that rule.

There are often columns that contain strings that are some sort of key values and are always in English (or your own language) and can’t be filled by the user itself (yes, a dimension table and substitude key would often enough be better, but …).

Phone numbers, international country codes, currency codes etc. are stored as VARCHAR often too.

It make no sense to user NVARCHAR here (you don’t want smileys or Chinese signs in the phone number and country / currency are standarized latin codes).

As others have said, when you should use nvarchar depends:

* A code comprised of only of digits? Obviously varchar.

* An app used only by a single US company that only does business in the US? Varchar is probably fine for every column.

* An app that might be used by companies or users outside the US. Nvarchar

What is overlooked in the “disk space is cheap” analysis is, “expanding disk space (or memory capacity) is cheaper than overhauling the app(s) (and dependencies) because you have to switch to nvarchar”.