Query Exercise Answers: Why Are These 3 Estimates So Wrong?

This week’s Query Exercise challenged you to figure out why these 3 estimates went so badly:

Transact-SQL

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

SELECT TOP 250 p.Id, p.Title, COUNT(*) AS VotesCast FROM dbo.Users u INNER JOIN dbo.Posts p ON u.Id = p.OwnerUserId INNER JOIN dbo.Votes v ON p.Id = v.PostId WHERE u.Location = 'Reading, United Kingdom' GROUP BY p.Id, p.Title ORDER BY COUNT(*) DESC; |

Even though I’ve got indexes on Users.Location, Posts.OwnerUserId, and Votes.PostId, the estimates were terribad:

I challenged you to explain why each of the estimates went badly, in order.

1. Why was the Users.Location estimate off?

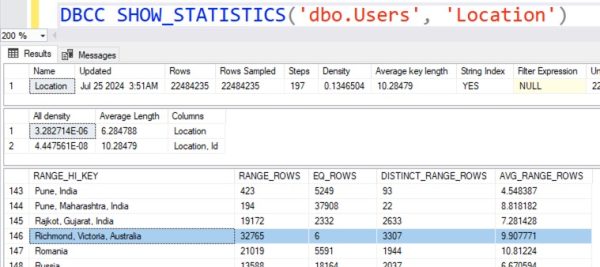

SQL Server opened the Users.Location statistics histogram and went looking for Reading, United Kingdom:

There wasn’t a dedicated histogram bucket for Reading here (nor is there one in the 2nd 200 that we created in the filtered stats attempt, because Reading isn’t in the top 400.)

The moral of the story here is that in complex, real-world queries, the filtered statistic solution for the 201 buckets problem isn’t enough. Even relatively “small” outliers like Reading run into problems. Now, that one estimation problem by itself wouldn’t be a big deal, but it turns out that Reading is an outlier in another way, as we’ll see next.

2. Why was the Posts.OwnerUserId estimate off?

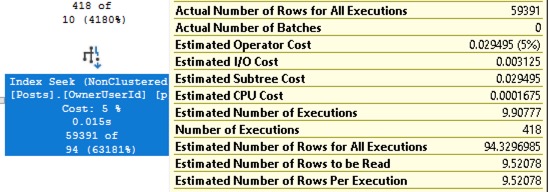

First, we need to understand where the estimate came from. Let’s hover our mouse over the Posts.OwnerUserId index seek:

I don’t understand what kind of drunken baboon was at the wheel when this tooltip was designed, so forgive me for having to restate the numbers in an order that makes some kind of logical sense:

- Estimated Number of Executions: 9.9 – because SQL Server thought ~10 people lived in Reading, and we would have to seek in here 10 times to find their 10 different User.Ids

- Estimated Number of Rows Per Execution – 9.5 – because SQL Server believes overall, in the entire user population, people who have created Posts, have created an average of 9.5 each.

It’s worth stopping here to elaborate a little more on that. SQL Server is not saying, “The people in Reading create an average of 9.5 posts each.” Until runtime, SQL Server has no idea who the people in Reading are – it doesn’t know their User.Ids! It doesn’t know anything special about Reading whatsoever. It’s assuming the people in Reading are all average – and it turns out they are not.

- Actual Number of Executions – 418 – because when we did the Users index seek, we brought back way more rows

- Actual Number of Rows for All Executions – 59,391 – and this is where things really go off the rails.

If SQL Server’s estimate that each person produces an average 9.5 posts was correct, then 418 * 9.5 = 3,971. We’d have found about 3,971 posts for the people in Reading. However, that’s still way off, because we found more than 10x that many!

It turns out that some individual people in Reading are outliers, particularly one Jon Skeet. Lil Jon Skeet Skeet, we call him. When he’s not in the club, he’s answering Stack Overflow questions, so he massively inflates the number of Posts.

3. Why was the Votes.PostId estimate off?

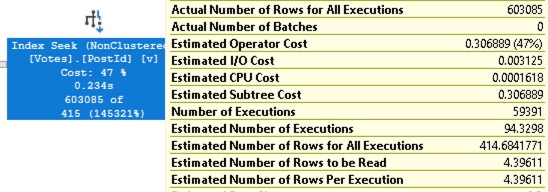

Again, let’s understand where the estimate is coming from by hovering our mouse over that operator:

- Estimated Number of Executions: 94 – because SQL Server thought the 9.9 people in Reading would only produce 9.5 posts each, and 9.9 * 9.5 = 94

- Estimated Number of Rows Per Execution – SQL Server believes the average post from anywhere receives 4.4 votes

That might be true for overall – but if we look at just the posts from Reading:

Transact-SQL

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

WITH PostsFromReading AS ( SELECT p.Id, COUNT(*) * 1.0 AS VotesCast FROM dbo.Users u INNER JOIN dbo.Posts p ON u.Id = p.OwnerUserId INNER JOIN dbo.Votes v ON p.Id = v.PostId WHERE u.Location = 'Reading, United Kingdom' GROUP BY p.Id) SELECT AVG(VotesCast) AS AvgVotesCast FROM PostsFromReading; |

We get an average votes cast of 11.6 – more than double the global average! There’s something about the Reading posts that drive people wild. (Skeet skeet.)

So for the final estimate, Estimated Number of Rows for All Executions = 414, we can see why that’s way off. It’s composed of 3 parts: 10 people in Reading, 9.5 posts each, 4.4 votes per post. All of those component estimates were wrong: there were more people, with more posts, and more votes on each post. The final estimate is 1,453x off.

If you figured out these causes, you should be proud of yourself.

Seriously, take a moment to congratulate yourself on your journey. You were able to read the execution plan, decipher the goofily-displayed metrics, and understand the components that drove each estimate. You understood where the statistics came from, and why even hacked-together solutions for the 201-bucket problem aren’t enough. You understood that joins literally multiply bad estimates.

If you didn’t figure this stuff out because you’re used to working with relatively small data sets, perhaps with nicely evenly-distributed data, you should also breathe a sigh of relief! Your career hasn’t progressed to the point where you’ve had to solve these problems, and it’s gotta be nice to smile and nod from the outside at what the rest of us have to deal with.

When you’re ready to learn more about solving these kinds of problems, check out my Mastering Query Tuning class. We cover lots of estimation problems like these and dig into various ways to fix it.

When you’re ready to learn more about solving these kinds of problems, check out my Mastering Query Tuning class. We cover lots of estimation problems like these and dig into various ways to fix it.

You shouldn’t jump to that class first: the prerequisites include my Fundamentals of Query Tuning class and Mastering Index Tuning class. I really do get students who jump directly to one of the more advanced Mastering classes, and then come back to me saying, “Uh, Brent, I thought I was experienced enough to jump straight to that, but it turns out I didn’t actually know the fundamentals that I thought I did.”

That’s why most students start with the Fundamentals bundle, then after their first year, step up to the Mastering bundle. Don’t jump straight to the Mastering one if you don’t have a lot of time to spend digging into the classes – start with the cheaper Fundamentals one, and only spend more when you’ve conquered the basics.

See you in class!

Related

Hi! I’m Brent Ozar.

I make Microsoft SQL Server go faster. I love teaching, travel, cars, and laughing. I’m based out of Las Vegas. He/him. I teach SQL Server training classes, or if you haven’t got time for the pain, I’m available for consulting too.

Get Free SQL Stuff

"*" indicates required fields

5 Comments. Leave new

[…] comments. Check out the solutions from other folks, compare and contrast your work, then check out my post with the answers. Have […]

What

What an incredible display of the madness that is required to understand why SQL does what it does! Your example is so well constructed to make it clear how much we need to know to troubleshoot these problems effectively. I didn’t even know what I didn’t know.

Awww, thanks!

[…] Query Exercise Answers: Why Are These 3 Estimates So Wrong? (Brent Ozar) […]