Getting Data Out of an Audit Table: Answers & Discussion

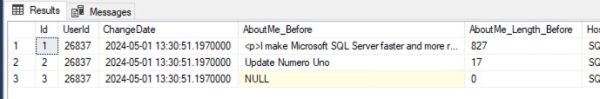

In last week’s post, I gave you a trigger that populated a history table with all changes to the Users.AboutMe column. It was your job to write a T-SQL query that turned these Users_Changes audit table rows:

Into the full before & after data for each change, like the earlier query from the blog post:

The trigger will always log the “before” values into the Users_Changes table, but the “after” value could be in a few different places:

- If other changes have been made to that row, then the “after” value will be the next change for this Users.Id in the Users_Changes table

- If no other changes have been made to that row, then the “after” value is the current state of the row in the Users table

- If the row has since been DELETED, the “after” value isn’t anywhere!

To test your own code alongside mine, run these changes:

Transact-SQL

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

/* Make some changes: */ UPDATE dbo.Users SET AboutMe = 'Update Numero Uno' WHERE Id = 26837; UPDATE dbo.Users SET AboutMe = NULL WHERE Id = 26837; UPDATE dbo.Users SET AboutMe = 'Update Part 3' WHERE Id = 26837; DELETE dbo.Users WHERE Id = 26837; GO SELECT * FROM dbo.Users_Changes; |

I didn’t explicitly call the DELETE scenario out in the challenge, and to be honest, I didn’t expect anyone to think of it when they were writing their answers. The post was all about catching mangled changes to the Users.AboutMe column, and the post’s trigger focused on updates of Users rows, not deletions. However, it’s still perfectly valid for someone to delete a row – and ideally, our query should be able to handle that situation. We didn’t get an answer that returned accurate data in that scenario, and I don’t blame y’all.

It’s an edge case – and it’s even harder of an edge case to handle than it might seem once you factor in NULLs. Let’s think about possible changes:

- The UPDATE might have set the row’s contents to NULL, in which case we want the AboutMe_After to show NULL.

- The UPDATE might have set the row’s contents to something, but then the row was subsequently deleted (and our trigger didn’t catch that) – in which case we want the AboutMe_After to reflect that we don’t know what the UPDATE did. NULL isn’t a valid answer here because it implies that the UPDATE set the AboutMe to NULL, which isn’t necessarily true. We want to show something like a “(Unknown, Row Has Been Deleted)” warning.

So that means we can’t just slap a COALESCE in there and call it a day. We’re gonna need some tricky CASE statements.

Here’s the query I came up with, and note that I’m including the different AboutMe_v2 and AboutMe_Current data just for diagnostic purposes so you can see how NULL handling is tricky:

Transact-SQL

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

SELECT v1.Id AS Users_Change_Id, v1.AboutMe_Before, v2.AboutMe_Before AS AboutMe_v2, u.AboutMe AS AboutMe_Current, CASE WHEN v2.Id IS NOT NULL THEN v2.AboutMe_Before WHEN u.Id IS NOT NULL THEN u.AboutMe WHEN u.Id IS NULL THEN '(Unknown, Row Has Been Deleted)' ELSE '(Unknown, My Query Messed Up)' END AS AboutMe_After FROM dbo.Users_Changes v1 LEFT OUTER JOIN dbo.Users u ON v1.UserId = u.Id LEFT OUTER JOIN dbo.Users_Changes v2 ON v1.UserId = v2.UserId AND v1.Id < v2.Id AND v1.ChangeDate <= v2.ChangeDate LEFT OUTER JOIN dbo.Users_Changes vBetween ON v1.UserId = vBetween.UserId AND v1.Id < vBetween.Id AND vBetween.Id < v2.Id AND v1.ChangeDate <= vBetween.ChangeDate AND vBetween.ChangeDate <= v2.ChangeDate WHERE vBetween.Id IS NULL ORDER BY v1.ChangeDate; |

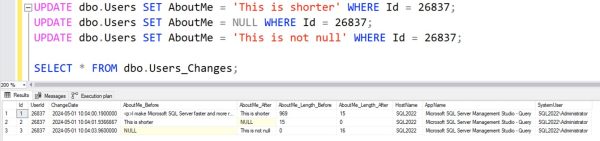

Which, when auditing this series of changes:

Transact-SQL

|

1 2 3 4 |

UPDATE dbo.Users SET AboutMe = 'Update Numero Uno' WHERE Id = 26837; UPDATE dbo.Users SET AboutMe = NULL WHERE Id = 26837; UPDATE dbo.Users SET AboutMe = 'Update Part 3' WHERE Id = 26837; DELETE dbo.Users WHERE Id = 26837; |

Comes up with these results:

Notice how rows 2 & 3 both have nulls for the v2 and Current columns, but they have different results for AboutMe_After? That’s because the 2nd update statement actually did set AboutMe to NULL, and we do have a Users_Change row that knows about it (from Users_Change_Id = 3.)

In production, if I was faced with this problem, I’d probably want to change the trigger itself to log deleted rows as well as updated ones. However, I found this to be a really fun exercise because I was faced with this exact problem at a client – we were auditing past data whose changes had already been made, and I couldn’t build the historical data retroactively after the changes had been made.

Related

Hi! I’m Brent Ozar.

I make Microsoft SQL Server go faster. I love teaching, travel, cars, and laughing. I’m based out of Las Vegas. He/him. I teach SQL Server training classes, or if you haven’t got time for the pain, I’m available for consulting too.

Get Free SQL Stuff

"*" indicates required fields

4 Comments. Leave new

Hi Brent. I am a long-time reader and first-time commenter.

I am curious why you chose to use both Id and ChangeDate in your join predicates to find the next changed row in the audit table.

If, for some reason, an Id was inserted out of sequence from the ChangeDate, then the row would be excluded by your predicates.

If the ChangedDate always follows the Id, then where is the benefit of joining on both columns?

BTW, I love the inclusion of the vBetween join to ensure that we only get adjacent changes. My thoughts were to use window functions eg LEAD to get the next change row, and since this is a debugging query I thought this would have been asimpler solution than joining to the change table 3 times. But I bow to your wisdom and creativity.

Oh that’s a really good question and I forgot to elaborate on it in the post. I wanted to write it in a way that people could either use integers or GUIDs as their clustered index and/or primary key. If you’re using GUIDs as PKs because, say, you’re doing bidirectional replication and you’re doing updates in multiple locations, then you’d want to join solely on ChangeDate. Otherwise, just use the Id.

Hi Brent, I found an alternative solution to the problem. I posted it on PasteBin here:

https://pastebin.com/nf7prY1K

Long story short, instead of having to wrangle with weird case statements and join predicates, just append the live data as an ‘audit’, with a flag to delete it later. Then, use the LEAD function, and delete the flagged row.

I’m still a beginner in TSQL, so there’s probably something I’ve missed. I’d appreciate your thoughts on this.

Hi! Unfortunately due to the amount of emails I get, I can’t do free code reviews months after a blog post goes live – hope that’s fair. Cheers!